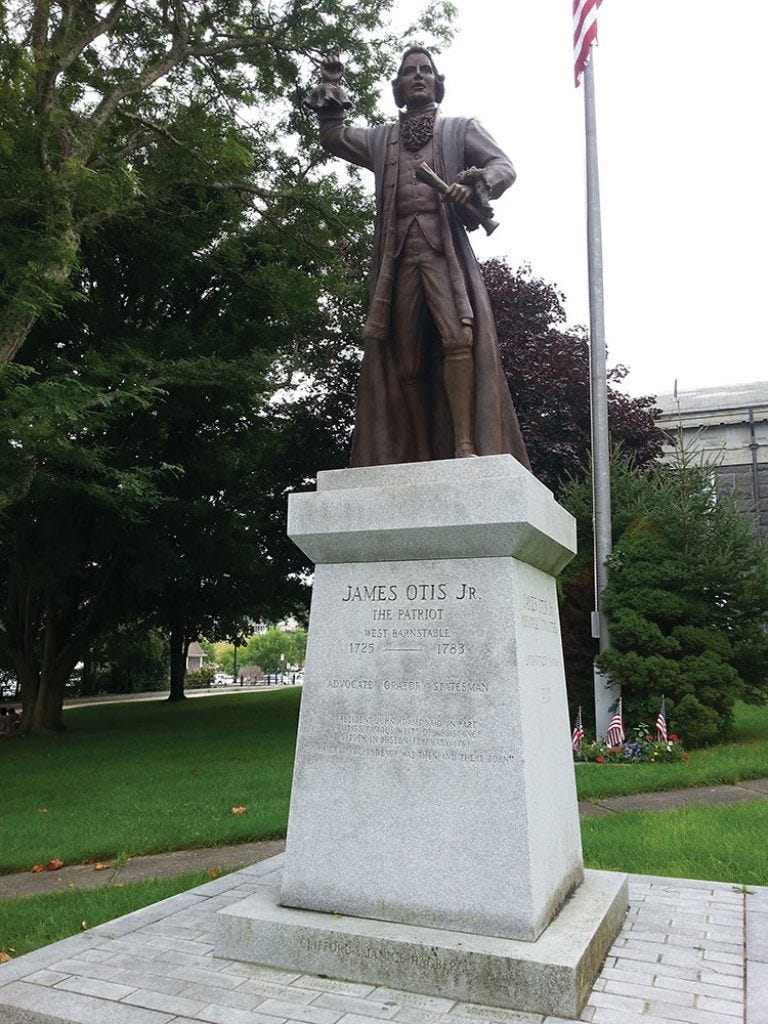

Forgotten Founder and Hero of the Nascent American Revolution: James Otis

Influential and Strange, in Life and in Death

James Otis is an American founder that few outside of the world of academic American history have heard of. This is a shame, and this writer seeks to correct this injustice in the small way that I can, by providing a brief but colorful biography of the man. One that reflects his extraordinary influence upon the American Revolution, and also speaks to the man’s colorful life and tragic death.

James Otis Jr. was the son of, naturally, James Otis Sr. The junior Otis was a Boston lawyer and was held in high esteem during his career, which overlapped with and informed what American historians call the Imperial Crisis, the era of ten to fifteen years in Colonial America leading up to the American Revolution. This era saw colonists resist excessive laws and taxes, imposed on them from England. It was, in fact, James Otis who famously stated, “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” This soon gave life to the cry of colonial resistance: “No Taxation Without Representation,” a phrase which too many Americans today do not actually understand the context of. This will be explained in due course.

In 1765, the English Parliament imposed the Stamp Act upon the American Colonies. Though this was not the first new imposition of taxation from three thousand miles away (the Sugar Act, imposed the year before in 1764, was the first but had far less impact and yielded far less of a negative response), the Stamp Act angered many. Not only was the Stamp Tax far and wide in it's reach, requiring a stamp on virtually all pieces of paper and paper-made products, from legal papers to playing cards, but it was a tax imposed on the meager worker to the successful lawyer. It was because the tax was burdensome on so many, and especially on business owners and attorneys (both of whom dealt especially with a high volume of papers which required the “dreaded stamp”) meant that the poor and the rich, the economically lowly as well as the wealthy, found common cause against the mother country and its new policies of imposing laws and taxes directly from Parliament.

To enforce and police the proper use of the Stamp, British soldiers were authorized to use something already on the books: Writs of Assistance, which were self-authorizing warrants (signed and issued by the searching officers themselves without the need to seek approval from a neutral arbiter). After the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, this policy allowed the soldiers to enter private property, including ships, businesses, and homes, to ensure that colonists were utilizing the stamps, as prescribed by law.

It was in 1761, in his role as a Boston lawyer, that Otis first stood up against Writs of Assistance. A few years later, in the wake of the Stamp Act, Otis made the now famous argument of no taxation without representation. Otis was, of course, personally impacted by the law, but kept his arguments aimed at the principle that the Writs of Assistance were a violation of liberty, and now given particular power by an unjust tax.

John Adams, another Boston lawyer who over the coming years grew in prominence and eventually gave legal reasonings for revolution, later stated that James Otis’s proclamations against the Writs of Assistance were the first fires of what became the battle for American independence.

Otis kept his arguments aimed at the principle that the Writs of Assistance were a violation of liberty, and now given particular power by an unjust tax [the Stamp Act].

In the same era, Otis advocated for the freedom of African Americans as well as Euro-Americans, in his pamphlet, The Rights of British Colonies, Asserted and Proved. Here again, Otis was ahead of his time, compared to most of his contemporaries.

James Otis would not, however, live past the revolution he ultimately influenced. He had been known, to his family and friends, as occasionally emotionally unwell and unstable, but this disposition was not constant. It was a condition that those close to him could generally tolerate without incident. This would change in 1769, however, when he was beaten by British crown officer and tax collector, John Robinson. Robinson violently gashed Otis’s head with a cane and beat him mercilessly. The physical pain and psychological trauma related to the experience appeared to seriously exacerbate Otis’s already compromised mental health.

By the early 1780s, in the final years of the American Revolution (the last major battle of the war was at Yorktown in 1781), Otis's unique contribution to the changing state of his country was beginning to be a bit of a distant memory, as other men rose to prominence in the 1770s and 1780s, including Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Otis’s fellow Bostonian friend, John Adams.

And yet, it was Otis who articulated the first and arguably most important principle of the entire revolution: that taxation without representation is tyranny.

But what did James Otis mean by this? It does not mean what many, perhaps most, Americans today believe it to have meant.

Too often it is stated, including by public figures, that the American Colonists eventually sought revolution because they had been deprived (and had been seeking) representation in the British Parliament. This could not be further from the truth. I have spent countless hours clarifying this in countless college classrooms and lecture halls, and will do so until my last breath.

The representation Otis and the colonists were referencing was not a desire for a place in the Parliament. The argument was that colonists already had such representation, in the form of their local colonial assemblies. For James Otis (and others), the Massachusetts Assembly was the equal of the British Parliament, as was Virginia’s House of Burgesses for the people of Virginia Colony, etc. Each colony had its own equivalent of Parliament, in the form of its Assembly. This is one of the most important, and least understood, facets of the American Revolution.

James Otis famously stated, “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” This soon gave life to the cry of colonial resistance: “No Taxation Without Representation,” a phrase which too many Americans today do not actually understand the context of…

The representation Otis and the colonists were referencing was not a desire for a place in the Parliament. The argument was that colonists already had such representation, in the form of their local colonial assemblies… This is one of the most important, and least understood, facets of the American Revolution.

For evidence of this, one need only to look to the Declaration of Independence. That historical document that was a declaration TO THE WORLD, AND ABOUT THE ENGLISH KING, and demonstrates how little the Americans regarded England’s Parliament. Through the entire list of grievances, they barely mention the British representative body. When the Declaration does finally refer to it, it does so with the dismissive designation, “their [England’s] legislature,” clearly affirming the Parliament to not be the representative body of those in the colonies-turned-independent states. It never was, they argued, and the Americans never wanted it to be.

In 1783, the same year American independence was made official to the world with the Treaty of Paris, James Otis was visiting a friend in Andover, Massachusetts. He had long since lost the influence he exhibited twenty years earlier, when he stood against the Writs of Assistance, the Stamp Act, and other forms of British tyranny, and unknowingly igniting a resistance that would evolve—over time—into a revolution.

As James Otis spoke with a friend that day in Andover in 1783, standing in his friend’s front doorway, he was suddenly struck by lightning in the midst of their conversation. He collapsed and died instantly. Literally, in a flash, James Otis left this mortal coil.

Considering the incredible influence he made during the Imperial Crisis, the unfortunate amplifying of his mental problems as a result of a physical assault by a British officer, and the strange circumstances of his death at the moment American independence was realized, there is a lot to take in about the life and death of James Otis.

Adding to the strangeness of his incredible life story, Otis had actually stated years earlier to his younger sister, playwright and political essayist Mercy Otis Warren, that when it was his time, he wanted to die by the strike of a bolt of lightning. A strange thing to say, in his time or any, and stranger still for it to have ultimately transpired.

James Otis was an inspiration to those who became America’s revolutionary founders. As the mission of independence grew stronger, his faculties grew weaker. When he died, it was dramatic, sudden, and—incredibly—exactly what he had said he wanted.

He is worth remembering, for his life, his death, and his impact upon what became the American Revolution and the United States of America.

[James M. Masnov is a Columbian Distinguished Fellow at George Washington University in Washington, DC. He has been a contributor at Pure Insights, the Brownstone Institute, Armstrong Journal of History, and the Oregon Encyclopedia, among other publications. His books include Rights Reign Supreme: An Intellectual History of Judicial Review and the Supreme Court, available here, History Killers and Other Essays by an Intellectual Historian, available here, and Imperfect Vehicles, available here.]

Are you a fan of history? Can’t get enough and need so much more? Consider becoming a free or paying subscriber at the History is Human Journal, a publication which seeks to provide nonpartisan scholarship that is neither cynical nor utopian. Help us make history!

Subscribe here.