Thoughts in the Margins, Part Six: Never Losing Sight of the Main Objective, Peer Review, Revise-Revise-Revise, and Final Thoughts

Concluding Installment of a Multi-Part Series about Writing Compelling Nonfiction

Welcome to the concluding section of the “Thoughts in the Margins” series about writing compelling and effective nonfiction. As previous segments have shared ideas about the importance of organization and imagination, this conclusion shares some images that capture this writer’s journey from idea-to-project-to-thesis-to-book. It is sincerely hoped that this series is, and has been, useful for potential and promising writers looking for some level of inspiration and guidance.

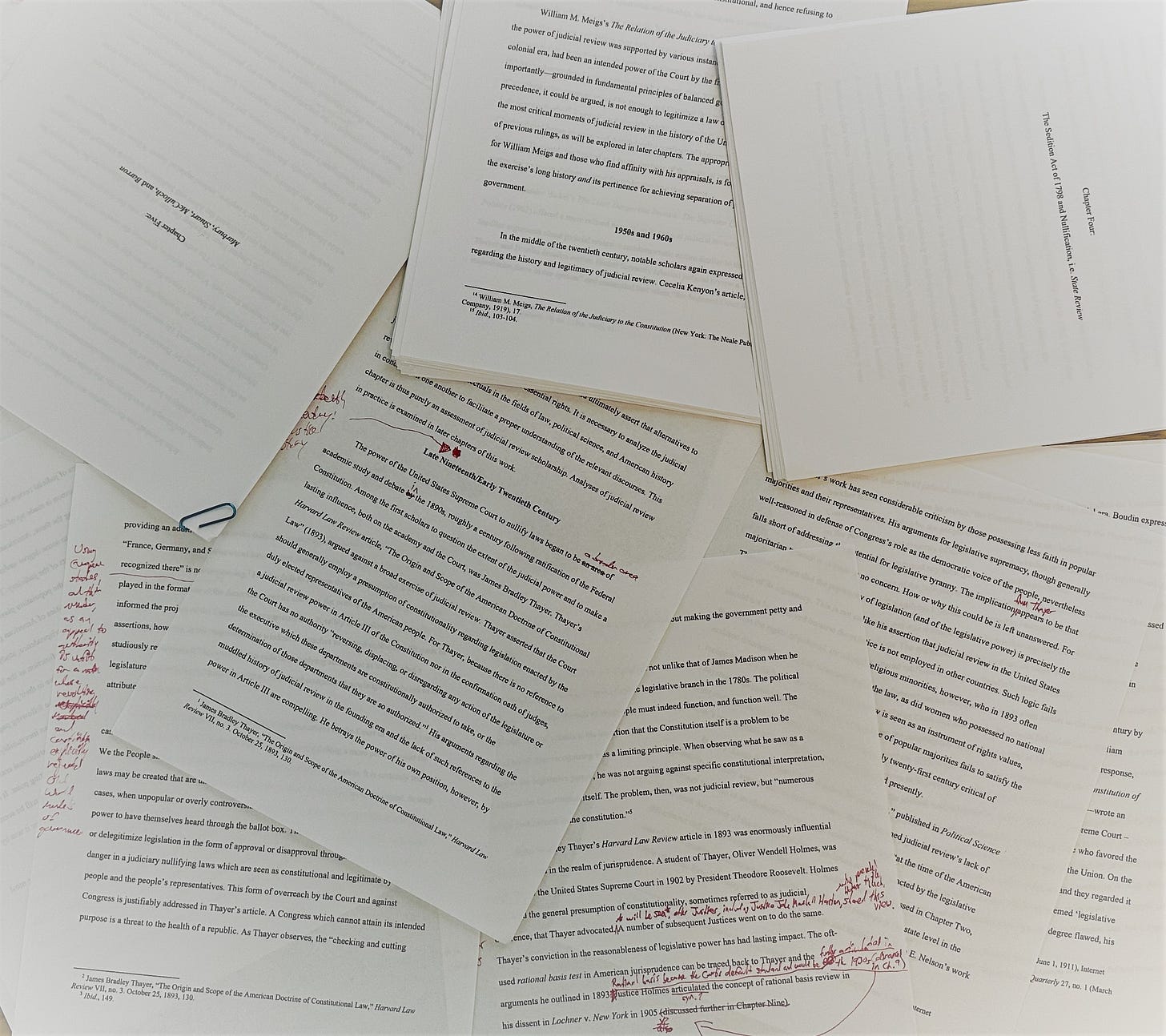

Let prior work inform your current project. In my case, I had considerable research and writing from graduate school and even undergrad courses that proved useful to the writing of the master’s thesis and—eventually—the book. Those new to large projects like the writing of a long article or essay, a senior thesis, a master’s thesis, or a book, may discount or dismiss the significance prior projects (or even ideas) might play in the realization of a new, larger project. Not only is this method a good idea, but it is foolish to not benefit from work you may have already conducted. Even if your experience is not one connected to formal higher education or similar, regimented programs, it is possible you have pages filled in a notebook or device where you first jotted down ideas related to your project. Ideas often arise and form when we are least expecting them to. Because of this, it is not only a good idea to write down ideas as they come to you, but also to save anything you can for future use. It may surprise you how useful previous freewrites, notes, and brainstorming sessions may be. In the image above, this pile of papers is a collection of some (certainly not all) previous writings as well as notes from primary sources for my project. The papers that include a green post-it note attached are previous coursework, essays, articles, or writing ideas I discovered in my personal archive that contributed to the overall body of knowledge and data. Papers in white without green post-it notes are some of the numerous primary source notes I took in the process of researching for my project. Notice that some of these papers include my thoughts in the margins. Even as I was quoting primary sources, I would include questions and thoughts that arose when acquring this data. These thoughts in the margins acted as a guide for me when I eventually moved toward writing the initial drafts of chapters of the book.

Color-coding can be helpful in organizing different parts of projects or in keeping ideas in their appropriate categories. The first image above includes pages where certain primary source data was once thought to be useful for one chapter, but upon further research, became more relevant to a different chapter. Rather than trashing the work I had accomplished, or spending time re-writing to a new notebook or paper, I highlighted quotes and sources in green to note that they would be moved from one chapter to another (I specified by color what chapter the relevant data would be moved to). This meant that there was no loss of work, no wasting of time, and that the best arguments and observations that the sources could be used for would be utilized. Similarly, I color-coded pages to distinguish them between primary sources (and their relevant quotes) and secondary sources. The use of a quote bank is one of the most important and most organizing things a nonfiction writer can do. To get the best out of one’s research and quote bank, however, sources and their relevant quotes should be organized by the chapter they are likely to be used for (which is all the more reason why the entire arc—chapter by chapter—of the book should be outlined ahead of time) and organizing different chapter notes by color—and different types of sources (primary sources versus secondary sources) adds further to the organizing of the quote bank and, therefore, the entire organization of the research of your book or article.

Outlining the book into a chapter-by-chapter format prior to the beginning of research and writing is useful, but it is not where preparation of the writing or the organizing of ideas ends. It is also helpful to, when beginning the research and writing of a specific chapter, outline the chapter as well. Such an outline should only be about a page. Avoid making chapter-level outlines that cannot fit a single page. Otherwise, this may be a sign that the information you intend to present may be too much for a single chapter. This chapter outline provides a map so that you may trace your own progress and to be sure that your research is aligning with the focus of what you are aiming for as a writer. Because it is the nature of research (and new discoveries) to change the direction or focus of one’s work from time to time, this rough outline may easily change to some degree as a result of research. This is OK, and—in fact—it would be a sign of trouble if your research does not shift some of your focus and your ideas somewhat during the process, as the work of writing a book is also a process of learning for the author. For this reason, the outline may change and need to be resolved as new discoveries are made, and indeed some ideas may be discarded or deprioritized. This is all to be expected and is a natural process of the work. One nevertheless benefits from making a chapter-level outline, even as some of the details and focus shift over time. The outline presented in the image above, for example, is an early version that focuses primarily on subjects and themes—and wrestles with figuring out the order of which to present these things. As you continue to work on a chapter and research the relevant data and scholarship, you will revise this outline until it is something you can solidly work from as a writer.

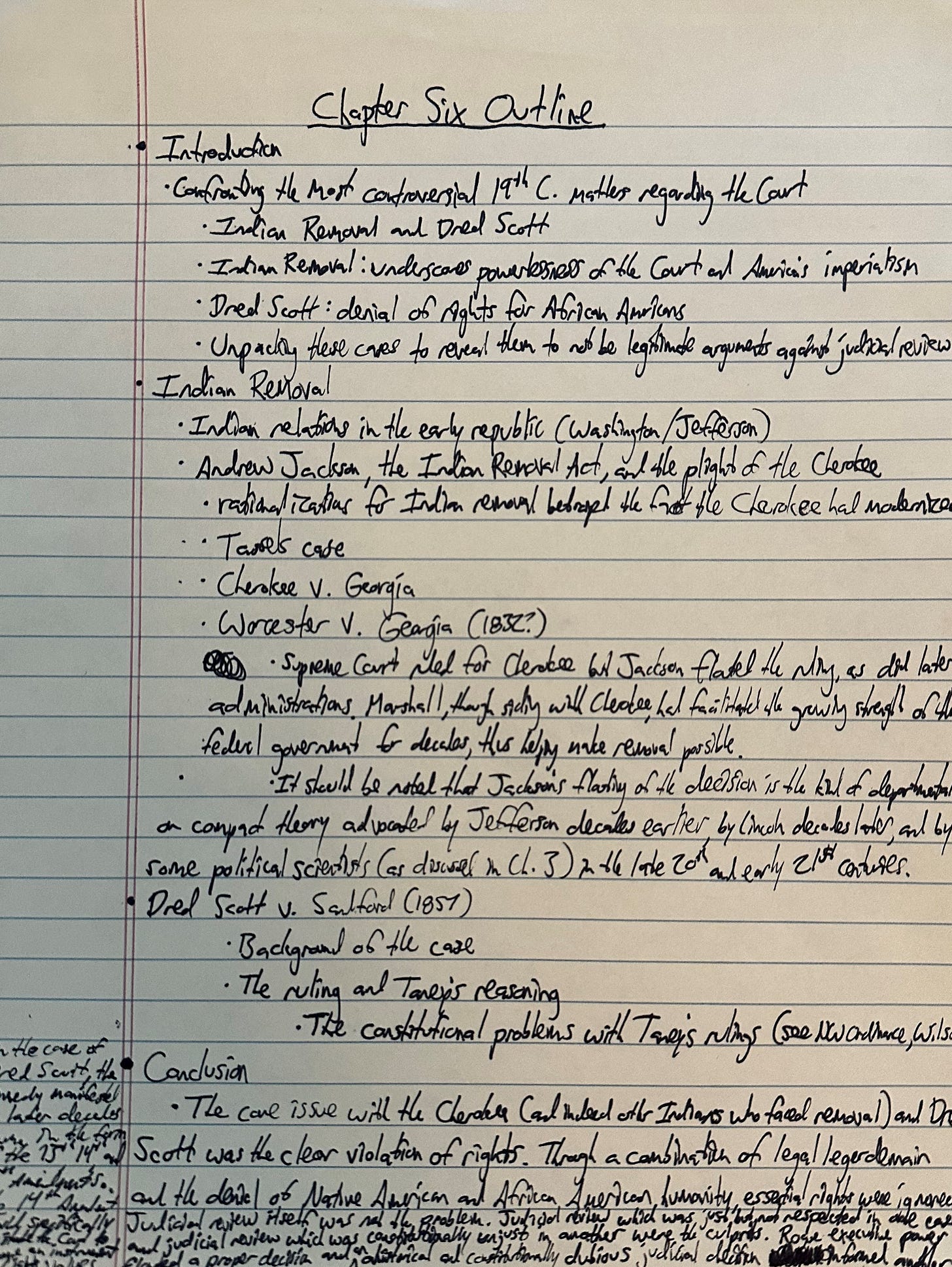

This chapter outline in the image above, despite the rough handwriting of yours truly, is a more refined and finalized outline of the chapter in the book addressing the controversies of Indian Removal policy in the nineteenth century and the Dred Scott decision which contributed to the Civil War. By this point, the chapter had been revised as a result of further research honing the focus and intent of the chapter. This is the reciprocal relationship between writing and research. At a basic level, we write to share our research, but our research also in fact informs our writing. Not just the topics we choose to write about, but the priority of how those topics are presented and how the history or information can be most compellingly shared.

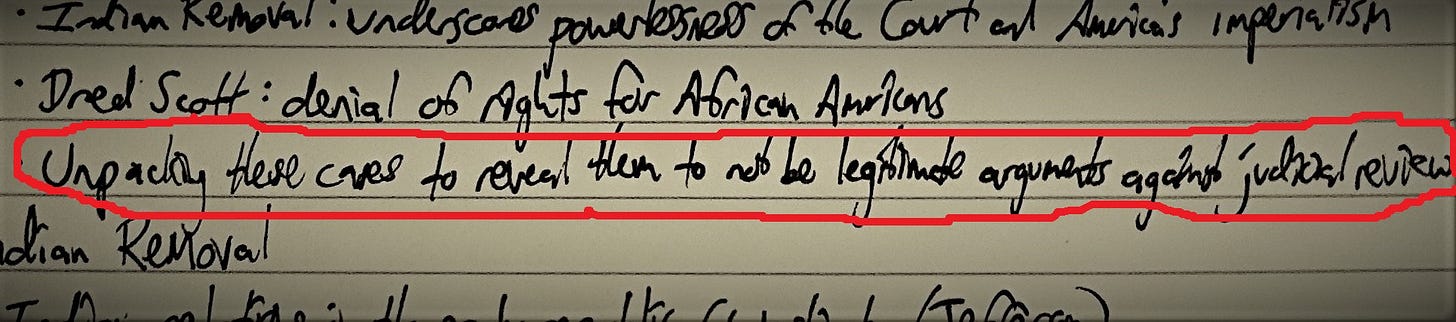

This excerpt, cropped and highlighted from the previous image, underscores that this chapter outline includes the thesis of the chapter as well. Whenever and wherever possible, a chapter level thesis should be included at every step, and that chapter-level thesis should contribute to the overarching thesis of the book. In this case, I included in the chapter outline, “Unpacking these cases to reveal them to not be legitimate arguments against judicial review.” This brings the focus of the entire chapter to be one of refuting counterarguments of my main thesis by addressing some of the the most controversial incidents related to the Court in U.S. History. It is for reasons like this that chapter-level outlines are so important. They offer an opportunity to provide further arguments and observations that bolster your position and make your project all the more compelling for your potential audience. When trying to find ways of bringing readers into your perspective, finding new ways of underscoring and strengthening the main objective of the work is a good way to go.

The above image displays the point at which each chapter has been written. The book is, by an outsider, finished. All of the chapters have been written.

In truth, I had just reached a new stage of the revision process. As can be seen in the above image, I added red pen revisions into the manuscript. This revision process followed the act of finishing a draft of the entire work, reading through the entire work, and making some modest changes. Here, after giving myself some time away from the work to allow some distance and perspective, I printed new copies of each separate chapter and spent a week or more making notes and noting revisions to be made. One week spent on further revisions for each chapter meant another considerable process of revisions, all of which prior to peer-review. Because the work initially acted as a master’s thesis, I benefitted from the peer-review of four PhDs (three historians, one of whom was also a lawyer and legal scholar, as well as one political scientist). After earning my master’s degree and converting the thesis into a manuscript to be sent to potential publishers, I put the entire work through a revision process again. I then sent it to another PhD historian I knew who had offered to spend the summer reading the work and offering further comments. Upon achieving a book deal with McFarland Press, I conducted still another revision process for the book, and then they also provided further peer-review during their process of converting the manuscript into a book. Not everyone will have the chance to undergo such rigorous peer-review from respected scholars and colleagues, but it is highly recommended to find peer review wherever you may find opportunities for it, from family members, friends, colleagues, co-workers, etc. Putting your work through the most rigorous peer review and allowing yourself the patience (and the time) it will take to do numerous revisions (even after you think you are finished) may make all the difference in how the work is treated by those in your field or by a general readership. Find peer-reviewers wherever you can, and then revise, revise, revise.

The final (after numerous revisions) version of the manuscript for Rights Reign Supreme.

Many do not realize that even after a book deal is secured, the final decisions regarding the title and the cover image are ultimately up to the publisher, not the author. The author can lobby for a particular title and a particular idea for a cover concept, but there is no guarantee that the publisher won’t decide on something very different from what the writer envisions. This can be very frustrating, but all the more reason to decide on the most compelling title and cover concept you can imagine. I was very fortunate that McFarland Books liked both my title and cover concept and those were what they went with. It is useful information for any would-be nonfiction author, then, to know that traditional publishers have final say on these very significant aspects of one’s book. As for seeking a traditional publisher, if that is desired, treat it like the job that it is—just as one should do with the writing and research of the book itself. It is time-consuming to reach out to agents and publishers, as each one has unique requirements for the submission process. Some first require a cover letter and a several-page summary of the book. Some may also ask to first see one or two sample chapters. Still others ask for submission of the full manuscript. It is helpful to know that each publisher’s request is unique to them and you want to respect each requirement to the letter, just to get your work considered, let alone accepted. Seeking publication can be a disheartening process, as one has already finished the actual book (minus some possible edits following a deal) and selling oneself and one’s work is not an easy or natural enterprise. Designate time every day or at least every week to submitting summaries/sample chapters/cover letters/full manuscripts to publishers and agents, but also leave psychological space to remind yourself that you are doing all that can be done and someone, somewhere may see the value in the work you have accomplished. Do not give up. Just as with the writing of the book itself, the time and effort required are worth it if you are consistent and determined.

Rights Reign Supreme: An Intellectual History of Judicial Review and the Supreme Court was published in 2023. Research started as early as 2020 (and, when including prior work that informed the project, even earlier). Writing of the book was primarily conducted in 2021, and final revisions and a book deal were secured in 2022. My experience is not unique, but many writers do not share how they navigate these processes, whether relating to research, writing, focus, passion, creativity, organization, peer-review, or pursuing a traditional publisher. It is hoped that this “Thoughts in the Margins” series might be useful for those currently (or those in the future) considering writing a compelling work of nonfiction. It is an extensive process that necessitates significant time, effort, and patience, but it is one worthwhile for those willing to do that which is essential to manifest a substantial, substantive, original work.

[James M. Masnov is a writer, historian, and lecturer. He has been a contributor at Past Tense, Pure Insights, the Brownstone Institute, Armstrong Journal of History, and the Oregon Encyclopedia, among other publications. His newest book, Rights Reign Supreme: An Intellectual History of Judicial Review and the Supreme Court, is available here. His first book, History Killers and Other Essays by an Intellectual Historian, is available here.]