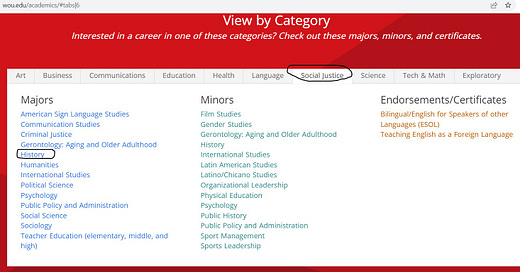

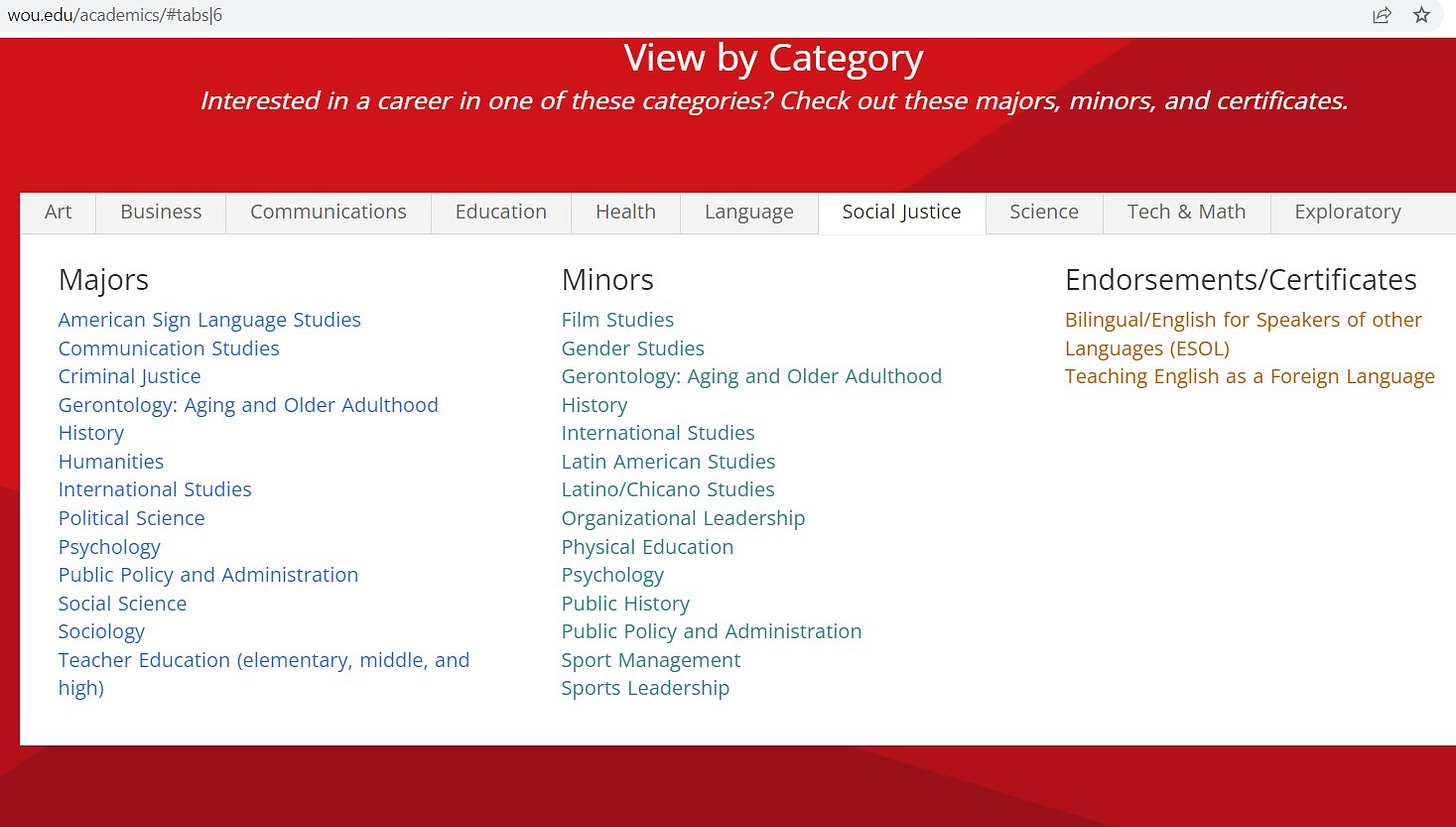

Western Oregon University placed its History program under the banner of "Social Justice"

Academic Categorizing? Or an Inherently Political Pursuit?

Though this writer has a personal stake in this story (I earned my bachelor’s degree from Western Oregon University years ago, prior to moving on to grad school and cultivating my career as a writer/historian/lecturer), this article addresses a larger set of questions that citizens, taxpayers, college students, faculty, administrators, and others all across the United States should contend with…

Is Social Justice an inherently political term? Or is it a broad academic term for fields that trace the development and mitigation of human relations, civilization, and fair treatment under the law?

Western Oregon University’s website, under its Academics tab, placed the field of History (and numerous other disciplines) under the banner of Social Justice. Was this appropriate?

The answer to this question, of course, rests in part upon the actual definition of the term.

Britannica’s definition is “the fair treatment and equitable status of all individuals and social groups within a state or society. The term also is used to refer to social, political, and economic institutions, laws, or policies that collectively afford such fairness and equity and is commonly applied to movements that seek fairness, equity, inclusion, self-determination, or other goals for currently or historically oppressed, exploited, or marginalized populations.”1

Merriam-Webster defines the term more succinctly: “a state or doctrine of egalitarianism.”2

University of Denver’s Graduate School of Social Work’s 2020 PhD graduate, Brittanie Atteberry Ash, asserts that social justice “means people from all identity groups have the same rights, opportunities, access to resources, and benefits. It acknowledges that historical inequalities exist and must be addressed and remedied through specific measures including advocacy to confront discrimination, oppression, and institutional inequalities, with a recognition that this process should be participatory, collaborative, inclusive of difference, and affirming of personal agency.”3

Some may dispute the framing or essence of any or all of these definitions (some have in fact noted, as will be seen, that social justice actually requires the unequal treatment of certain people), but giving the benefit of the doubt for a moment that these definitions are accurate, the question nevertheless remains as to whether social justice is itself an academic enterprise or a political one. If it is indeed political, does it belong as a term of scholarship in the academy?

Certainly, there are fields that use the term “justice,” such as the discipline of Criminal Justice. Criminal Justice, however politicized some may find certain adherents and participants to be, is nevertheless about the legitimate study of the American legal system, legal advocacy, incarceration statistics, etc. It is a field that offers useful data (and questions) to the world of scholarship. Does social justice do the same? Can it?

The Nobel-Prize winning economist, Frederick Hayek, criticized the term decades ago, both for its rather amorphous meaning as well as for its inherently unequal (and, therefore, illiberal) pursuit. He argued that the term was a “meaningless conception.”

Hayek observed, “Everybody talks about social justice, but if you ask people exactly what they mean by social justice, what they accept as justice, nobody knows. I’ve been trying for the last twenty years, asking people ‘What exactly are your principles?’”4

The issue with social justice is that it removes the liberal principle of individual rights and replaces it with tribal identity and collective rights. Even if one subscribes to matters related to reparations and other social justice-related movements, it should give one pause how the mission abandons principles connected to individual integrity.

Furthermore, and this was also Hayek’s point, social justice actually appears to require the unequal treatment of people:

“The classical demand is that the state ought to treat all people equally in spite of the fact that they are very unequal. You can’t deduce from this that because people are unequal you ought to treat them unequally in order to make them equal. And that’s what social justice amounts to. It’s a demand that the state should treat people differently in order to place them in the same position. . . .To make people equal a goal of governmental policy would force government to treat people very unequally indeed.”5

If one chooses to support the cause of social justice, regardless of its rejection of liberal principles like equal protection and individualism, the question remains as to whether the cause is one that can appropriately be suited to academic scholarship, even as merely a catch-all for the social sciences and/or humanities.

This begs the question: when institutions (public institutions, no less, funded—to some degree—with taxpayer dollars) like Western Oregon University posit the academic field of History under the banner of social justice, is this an innocuous categorization, or is it a statement of a political mission?

This begs a secondary question: how overtly political should an academic field or institution become?

When dealing with the complex world of interpersonal relations, law, government, the rise and fall of civilizations, war, democracies, republics, and authoritarian regimes, the field of history certainly gets tangled into political questions about representation, voting rights, state power, etc. Navigating these realms and doing so responsibly (which is very different from doing so neutrally; historians generally offer points of view in their work) is something that any good historian contends with on a regular basis. One can do so, however, regardless of worldview and regardless of whether one agrees with the framing of social justice by its advocates or not.

The larger question, then, is whether a higher education institution—particularly a public institution (private institutions, as privately-funded entities, enjoy the liberty to advocate whatever they may see fit, such as certain religious perspectives, ideologies, etc.) which is bound in trust to the public who funds it, should be advocating a seemingly political stance, however well-meaning it may be.

As someone who strongly believes in academic freedom, I am not interested in censoring any aspect of education or scholarship in higher ed. The question remains, however, as to whether social justice is an academic pursuit or a political one. The history has been quite clear on this: social justice has been the aim of political actors in history. Some of those actors may well have been scholars and professors, but that does not negate the implicit political aspect of social justice itself. Many clearly believe this is fine, but it does raise some possible concerns. If overtly political movements can wear the robe of scholarship in institutions of higher learning, what is the limiting principle to this idea? Again, this is a question coming from someone with no desire for academic censorship whatsoever, but it does seem like a reasonable question to ask.

The fact is that liberal education is itself—at its core—a philosophical enterprise. It follows the mission, however, in the case of the United States, of a constitutional republic that has enshrined the principle of individual rights and equal justice under the law into its founding charters. Public institutions that honor these principles, then, are merely honoring the principles of the nation, as set out in the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Reconstruction Amendments, and later additions to the charters of liberty.

Social justice, however, because of its implicit rejection of equal treatment of individuals, is arguably illiberal. Considering the issue in this manner, is it a political stance that is appropriate within public institutions that are funded by American citizens all across the political spectrum, including those who see it as something decidedly separate—indeed opposite—from the liberal principles of the nation? This is important to ask because it is not merely conservatives who have raised objections to the social justice movement, but also political independents, classical liberals, and disenchanted progressives who do not believe that it holds the same legitimacy as previous iterations, like the Civil Rights movement of the twentieth century.

Even if one agrees with the proclaimed aims of the social justice movement, is it nevertheless a political position? If so, unlike the traditional principles of American liberalism that actually informed and gave rise to higher education in the United States (including the principle of academic freedom), is social justice something appropriate for a public institution to explicitly advocate? Are there any political positions that are not appropriate for a taxpayer-funded institution to vocally support?

As this article has gone to some length to make clear, the controversy here is not social justice itself, nor even its merits. The question is whether it is appropriate for a publicly-funded university to treat social justice as though it is an apolitical term when many who fund that institution are likely to disagree.

Assertions that the term does not advocate an overtly political position but rather a collection of principles (as is often what supporters say) is—on the surface—sensible. Yet, it is difficult to pretend that causes related to Reparations, Defunding the Police, Ending Cash Bail, just to name a few (all of which have been declared under the banner of social justice in recent years), are not inherently political positions, whether one agrees with them or not. Some of these are also positions, regardless of what one thinks of them, that seem to strain the idea that social justice is about equal treatment.

This is why I ask—and this is a sincere question—was the use of Social Justice by Western Oregon University as an umbrella term for the social sciences and humanities appropriate or not? This is a question that is separate from whether one supports the broader social justice movement or specific causes under it.

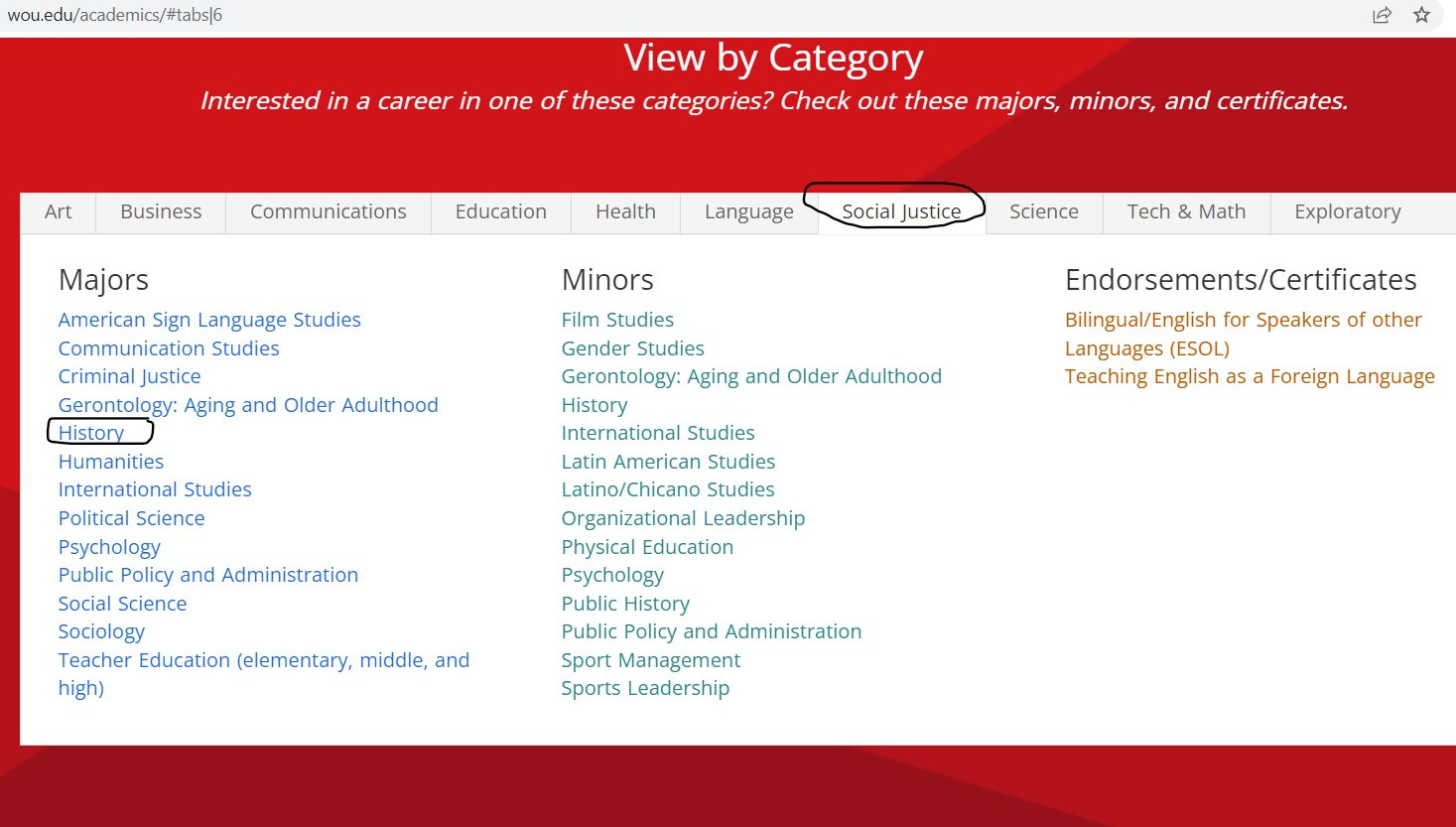

This writer reached out to the President of Western Oregon University, Jesse Peters, and—very much to his credit—he responded quickly and respectfully. He first mentioned that this decision was made and implemented a few years ago, and was the result of a recategorizing decision (by whom, he did not say, possibly the previous Provost?). He went on to say that “we have a new Provost coming on board and he will be reevaluating the web presence for academic programs.” While not the clearest answer (the motivation for this categorization was essentially absent), it is appreciated that President Peters—at least somewhat—addressed the question and did not seem to be particularly attached or devoted to the framing.

Peculiarly, and this writer does not want to take credit if it is not due, but between the time this article’s initial draft was being written (which was when yours truly reached out to the President of WOU) and the time this article was scheduled to be published, the WOU website was changed and the reference to Social Justice had been scrubbed from the university’s Academics page, where it had originally been found. Perhaps this change is a coincidence. Perhaps not.

It will do for now to merely note that while the overt appeals to social justice, whether that is appropriate or not in the realm of history (which is a debatable question, even if this historian sees problems with such framing), the fact that the term has been decoupled from the history program and other social science/humanities programs simply means that the social justice mission has gone (again) more under the radar. The social justice aims of WOU have since been nestled into its education department and other programs—which is where the social justice movement originally began in higher education several decades ago. While it is refreshing for this historian to no longer see academic history and social justice used under the same banner on Western Oregon University’s website, the fact that the term has returned to a more expected place is not necessarily a good sign. It may instead simply be a moment of self-conscious overreach on the part of the institution. If anything, the fact that such terms are no longer on the most easily accessible and most-used pages and have become associated with much more specific (but nonetheless very popular) majors, certifications, and programs, should give one pause. Besides, the pushing for social justice within the realm of public education and education programs is its own controversy and has its own long history.

As an academic historian who delves into political history and other related matters, it is understood that politics cannot be entirely removed from academic pursuits, nor should it be necessarily. There is a difference, however, between wrestling with questions related to political philosophy and how ideas manifest in societies, and an institution that seems to advocate a specific point of view through a very deliberate lexicon. The difference is all the more evident when it concerns a public institution that receives some of its revenue directly from taxpayers.

Additionally, regardless of one’s perspective, did it even make sense to use this term for these broad fields of study? What exactly was the purpose for doing so? Even when removed from academic history, should higher education really use a term like this in conjunction with academic programs that are so much broader and deeper than what the term implies? Is it acceptable considering that inherent and overt political advocacy seems to be the result? This is not a new question, but how does one walk the delicate balance between scholarship and politics? For myself, this is something I am always cognizant of, when writing articles and books, or especially when teaching in a college classroom. Perhaps the concerns of this writer derive from the fact that so many academics and educators don’t seem to ask themselves this very question.

Will the academic lexicon change again on websites like that of Western Oregon University’s when the next socio-political trend transpires? If so, what does it say about its priority to enduring liberal values like individual liberty and the rejection of generational or collective guilt? What are we to make of (particularly public) institutions that abandon these principles in favor of participating in fleeting ideological posturing? Even if one may be personally aligned with some of the aims of the social justice movement, the question persists regarding where intellectual inquiry ends and pure, unabashed activism begins. Is there some level of professional impropriety when professors and administrators conflate education with their personal politics? I am far from the first to ask this question.

One thing is certain: for as many people as there are who are enticed by terms like social justice, it also turns off and turns away equally meritorious scholars (both students and faculty) who prefer to keep the administration of higher education institutions apolitical, and who think that public institutions are particularly duty-bound to not be advocates for any one specific political ideology.

[James M. Masnov is a writer, historian, and lecturer. He has been a contributor at Past Tense, Pure Insights, the Brownstone Institute, Armstrong Journal of History, and the Oregon Encyclopedia, among other publications. His newest book, Rights Reign Supreme: An Intellectual History of Judicial Review and the Supreme Court, is available here. His first book, History Killers and Other Essays by an Intellectual Historian, is available here.]

https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-justice

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/social%20justice

https://socialwork.du.edu/news/defining-social-justice

https://fee.org/articles/hayek-social-justice-demands-the-unequal-treatment-of-individuals/

Ibid.