When Cowboys were Rock Stars

Old West Iconography and Meaning: its growth in the 1880s, its peak in the first half of the 20th Century, and its eventual decline, through Images and the Arts

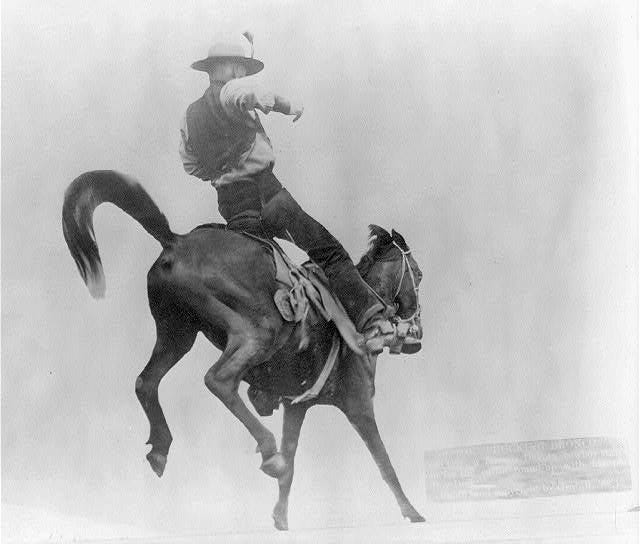

The American Cowboy represented the nation’s identity, and perception of itself, for the better part of a century, and—to a lesser degree—even longer. As an icon, it has been routinely mocked and celebrated in near-equal measure in the decades following the end of its cultural peak in the early 1960s. There may be current and recent iterations of Western/Cowboy-related films and television shows (Justified and Yellowstone, among others, come to mind), but nothing comes close to the centrality of cowboy culture and entertainment that prevailed from the 1880s to the 1960s.

What does the image of the cowboy and the American frontier exemplify? What are its best and worst iterations? Why did it loom so large and for so long in the American psyche, and what—if anything—replaced the cowboy as America’s avatar in the decades since? There exist no solid answers to such questions, but there is no doubt that the cowboy symbol is significant, in all of its variations, interpretations, and meanings.

Take a gander at the images below, and trace the evolution and transformation of depictions of the American West and the American Cowboy, from actual history to fictionalized portrayals.

At the dawn of the 20th Century, the West and the Cowboy—in reality and in fiction—began to be presented in new and growing mediums, including stage and screen.

Professor of Media and Culture at Utrecht University, Nanna Verhoeff, published her book in 2006 that examines the depiction of the West in early American film.

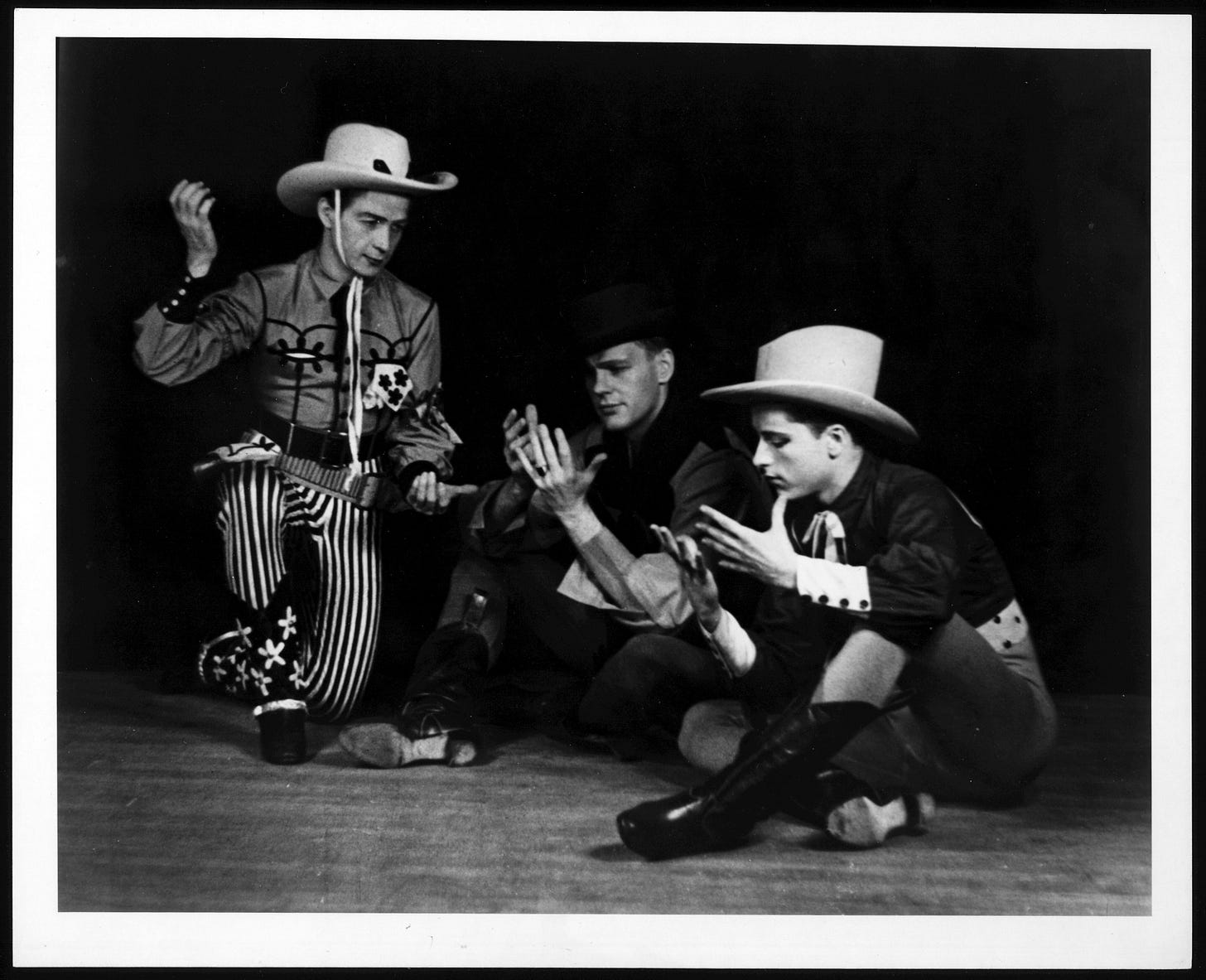

By the 1930s, depictions of the American West and the Cowboy went from cheap vaudeville to legitimate “high art” theatre. According to the Library of Congress, “In the mid-1930s [legendary composer, known as the Dean of American music, Aaron] Copland began to receive commissions from dance companies… His second commission… resulted in Billy the Kid (1938), one of his best-known works and the work which first definitely identified him with the American West.”1

Has anything replaced the Cowboy as America’s avatar? Or does the iconography serve as a placeholder for a time when such imagery acted as a means for how the nation saw itself, whether as a heroic individual or as an amoral entity? That is a matter of opinion, but one certainly worth a moment’s consideration. There is no doubt that the icon will endure, and likely continue to progress, regress, and morph endlessly in unforeseeable ways well into the future. Nevertheless, the concept of the American Cowboy will continue to wander yonder west, following the setting sun and searching for ever more frontier.

[James M. Masnov is a writer, historian, and lecturer. He is the author of Rights Reign Supreme: An Intellectual History of Judicial Review and the Supreme Court, available here. His first book, History Killers and Other Essays by an Intellectual Historian, is available here.]

https://www.loc.gov/collections/aaron-copland/articles-and-essays/about-aaron-coplands-works/music-for-dance-and-film/